What does burnout feels like?

Since I started working, I’ve felt the need to sprint and achieve as much as possible in the shortest amount of time. It’s a mix of anxiety about the future and low self-esteem, I think.

The point is that I’ve been working as hard as I could.

In general, I find myself having a “sprinting” attitude toward work, where I am extremely productive and focused for a specific period, followed by a dip in energy and focus. Not everyone is a fan of this strategy, as I’ve been told, “I have to be careful not to overstep into workaholism”.

To be honest, I’ve been asking myself if I am actually toxically attached to work, especially now that I’m experiencing another one of my LOW energy phases.

The sprints

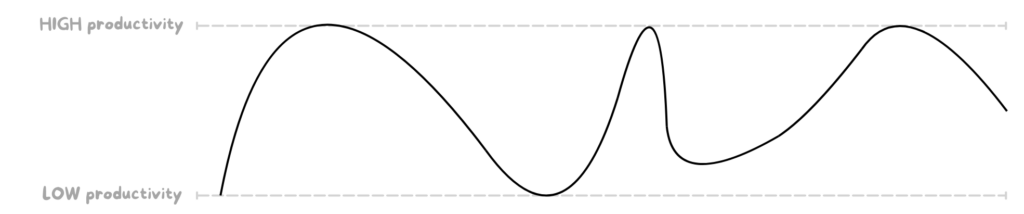

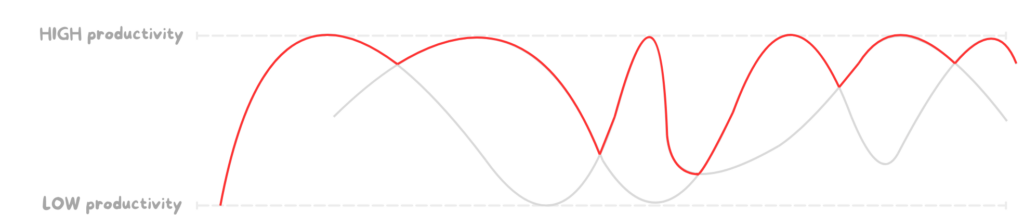

If I were to graphically represent the trend of a typical sprinting lifestyle, I would use a sinusoidal shape, with varying amplitudes, to illustrate how the duration of the productive phase is completely unpredictable.

In my current workplace, this mode of functioning has benefited me quite a lot. During my best days, I’m able to stay at my desk until I finish what I was meant to do. Over time, this has taught my colleagues that in case of an emergency, I’m the go-to person to ask.

I have achieved quite remarkable things in this HIGH state of being.

But it never lasts long; it is always followed by a period of demotivation, low energy, and cloudy days, similar to a slight hangover.

What I hate most about this second stage is the unfair judgment of the project I was working on, as if it suddenly lost all its value and interest, which leads me to abandon whatever I was doing in favor of mindless activities.

Basically, when I run out of juice, I feel like I’ve wasted it all on something useless and that I could have done a better job by choosing to do something else.

I often find myself wondering which of the two versions of myself is the wiser, but only during this specific LOW phase have I tried to define the problem and find a sustainable solution to ensure my projects can integrate into both my highs and lows.

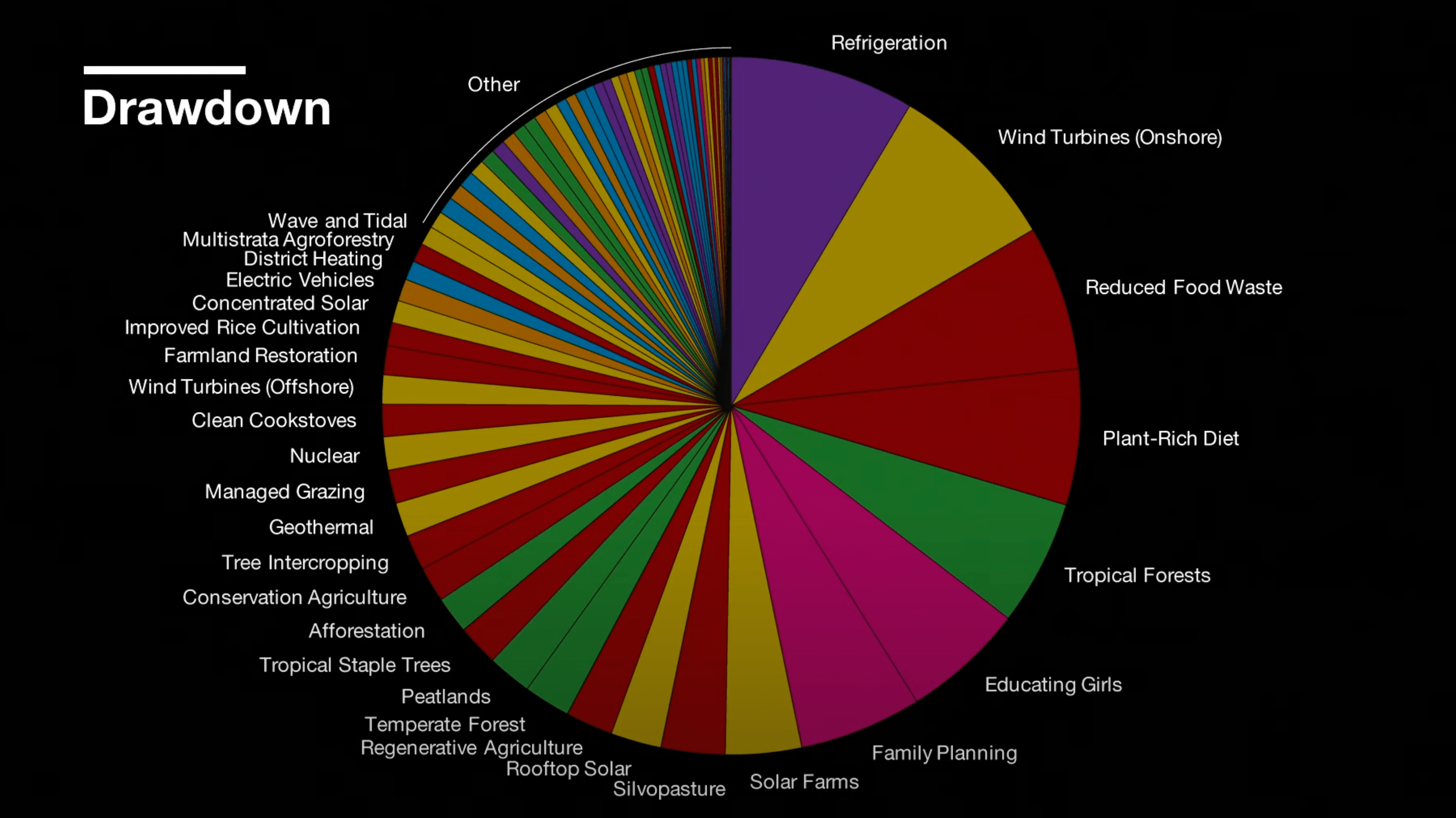

What is the”cost-opportunity”?

It’s a metric used in finance to compare the cost of something with its potential value if the money were instead invested in the stock market and compounded over the years.

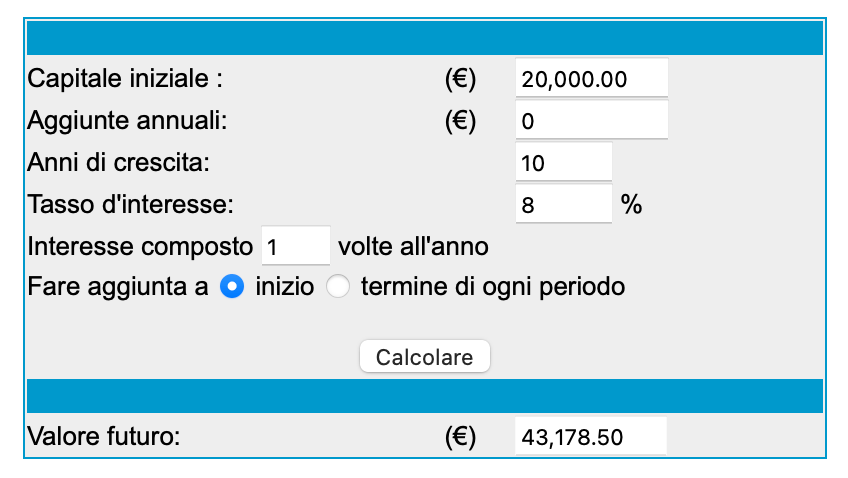

Compounding interest is quite a complex concept, but let’s just say that money has a potential value, which is calculated based on the expected returns of the stock market. For example, €20,000 invested in a stock portfolio with an average return of 8% per year over 10 years will amount to €43,178.50.

Crazy, right? More than doubled without doing anything!

So, when I decide whether to buy a €20,000 car, I ask myself if buying the car now has more value to me than having € 43,178.50 in 10 years.

Technically, if we were to judge purely from an economic perspective, the opportunity-cost of buying a car strongly favors NOT buying it, due to asset depreciation and stock market appreciation. Then, of course, we also have to consider non-measurable needs like “wanting to enjoy life,” which complicate the value assessment, but the concept still holds.

I’m using this metric to assess whether I’m investing my time and energy in a wise way, because, just like with money, I only have a finite amount of it.

Listening to the people closest to me, it seems that from the outside, I’m overdoing it, ignoring the price I’ll have to pay for it in the future.

As you can imagine, during the LOWs, my self-esteem drops to zero, and suddenly others’ opinions seem much more convincing than mine.

I tried to look into the topic, and I’ve managed to boil it down to three questions:

1. Is it smart to sprint at the beginning of my career, sacrificing on other things?

I suppose the answer to this first question varies based on what I want my life to be in 20 years…

Addressing the topic from a “capitalistic success” perspective is quite unpopular, especially considering we live in an era where the concept of “work-life balance” has gone viral. But I can’t help myself; it has never convinced me, sorry.

Digging into other people thoughts online, it’s quite easy to find convincing strategic arguments, I decided to quote the best sounding, even if they are not coming from the most authoritative of the sources available:

The DNA of your career and professional trajectory is disproportionately, unfairly, set by these early years. […] Balance is a myth. There are only trade-offs. Having balance at my age is a function of lacking it at your age. Your call.

Scott Galloway on profgalloway.com

The concept of deferred gratification is nothing new. […]. Rather than seek balance, they can front-load their professional efforts: find greater opportunities to break through the competition, accelerate their job prospects and eventually reach grander career heights. […] Galloway likens work-life balance to an investment: early, intense effort has to be given to work in order to buy the flexibility when it’s needed most. “The reality of investing is that it’s slow and boring,” he adds. “Healthy work-life balance is a tremendous benefit later in life – and it’s worth investing in that optionality as early as you can.”

Alex Christian on bbc.com

Sprinting at an unsustainable pace is an act of tremendous optimism, […].

Shyam Sankar on shyamsankar.com

Obviously, all of that holds true only if the “unsustainable pace” doesn’t take its toll before you get to the point where you can enjoy the benefits of the strategy. So, let’s move on to the next question.

2. Is it a sustainable plan?

Not really, at least not in the way I’m doing it.

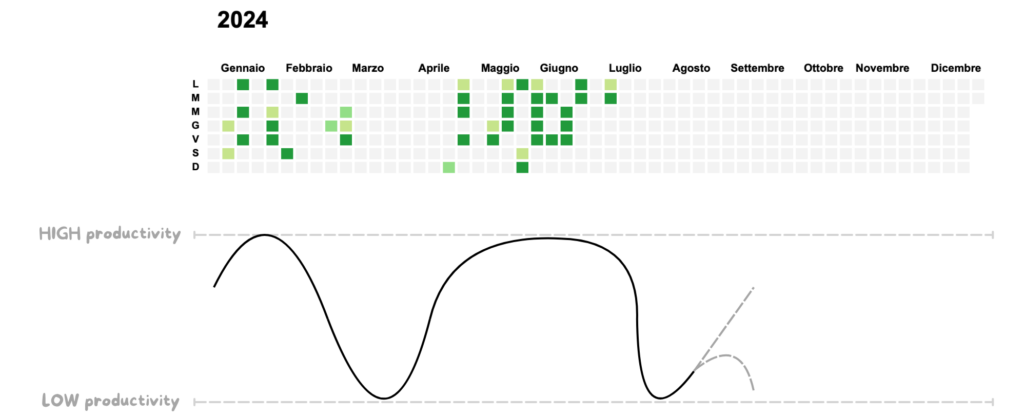

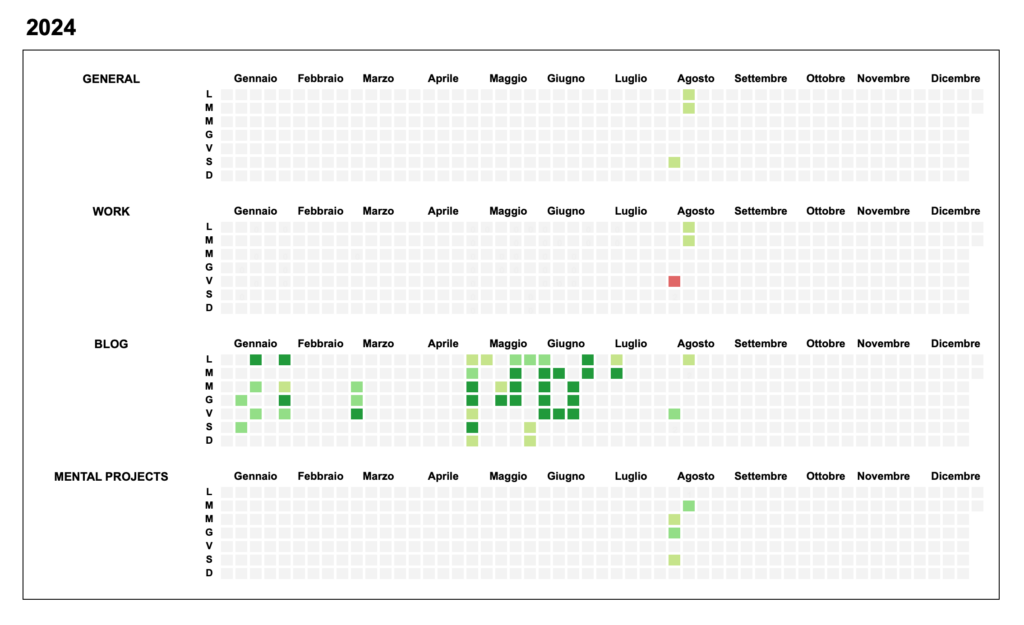

As I said before, I’m naturally a sprinter, and that influences everything I do, not just my job tasks. Let’s take the effort I’ve been putting into this blog as an example. If you look at the archive page, you can see the irregular frequency of my posting. There are months with multiple posts and entire months that aren’t even listed.

Plotted on a heatmap calendar, where every column is a week, it would look like this:

You don’t need to be a data analyst to notice that there are clearly two spikes in posting frequency, each followed by a period of complete silence, mainly caused by the natural LOW phase and a contemporary spike in work effort.

During the spikes, my work productivity curve was quite low, but when it needed to rise, it impacted the blog’s curve, ending the two different sprints.

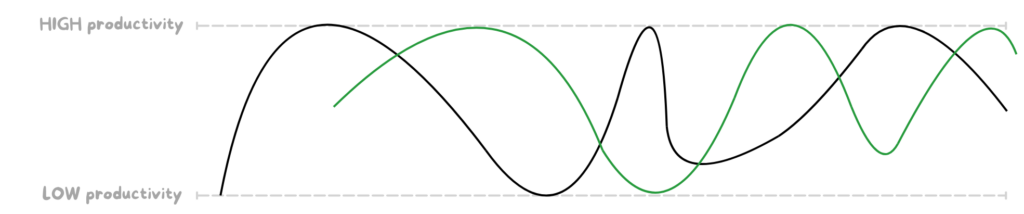

Going deeper, we could consider how the curves of many other aspects of my life are affecting each other, randomly halting sprints in various dimensions of my life. My financial plan is based on the same “initial sprint” concept.

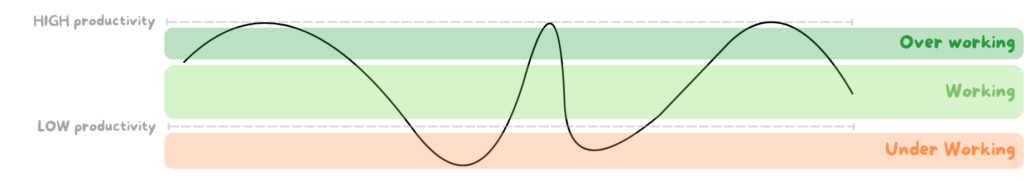

As balanced as it might seem, this is actually a recipe for burnout!

When you zoom out from individual projects to consider my overall energy levels, you may realize that if every time one sprint ends, another begins elsewhere, it means I’m always operating at a HIGH level, with the associated energy consumption.

To highlight the approximate1 result of the curve, I intersected and colored red the new curve, which, as you can see, is almost always in the high part of the graph.

Up until now, I’ve been kept afloat by weekends during which I would average 16 hours of sleep a day, just to restart all over again the following week.

So yeah, not really sustainable.

For that reason, I figured I needed to tweak something to make it work, and I got inspired by the title of an article I read while researching. The content itself wasn’t particularly interesting, but the title was: Overwork, Underwork, Repeat […].

Genius, to be honest!

Since I don’t want to use the quote as it is, I’ll take the opportunity to add a word that helps indicate when the overworking phase should transition to the underworking phase. I decided to use the moment I hit my goal as the point of transition.

So, the new version would be: Overwork, Hit, Underwork, Repeat.

You see, when I’m in the low zone of my performance, from the outside, people would still consider it more than acceptable work. The title of that article made me think I should dial down that low phase just a bit so that I could regain some extra energy from there!

Clearly, it’s not going to happen on its own, I’ll need to force these adjustments on myself.

So, let’s move on to the next question and explore what I could do to succeed in learning how to underwork.

3. How can i get the most out of this strategy?

First of all, I desperately need a way to monitor the flow of the different curves throughout the weeks so that I can recognize the beginning of a sprint and plan the necessary rest right after that.

For this reason, I repurposed the heatmap I already used to visualize the frequency of my blog posts, creating a Google Sheet with four different calendars, one for each of my main activities:

- General, used as a control chart

- Blog

- Work

- Mental Projects

For each category, I can input a score from 0 to 5, where 0 represents the underworking phase, while 5 is the spike of overworking.

If monitored daily, this should help me get a clear picture of my energy expenditures, allowing me to intervene and rest more when needed, even if my body doesn’t request it.

To ensure I keep inputting the scores regularly, I created a Google Form directly connected to the Google Sheet and set an alarm that reminds me to review the day every day at 23:00.

For now, I’m limiting myself to setting maximum levels of work without specifying any lower limit, but I suspect it will be necessary to ensure I’m dedicating enough time to each of my interests as they grow, multiply, and change.

Overwork, Hit, Underwork, Repeat. If it works, there’s not any doubt it’s going to make the my energy allocation way more sustainable, maximizing the cost-opportunity of my time as a young adult.

I’ll do my best to keep this as a mantra and not let it become my downfall. I’ll keep you updated!

- I just highlighted the highest curve, point by point, simplifying out the value of effort in the lowest curve. ↩︎

Lascia un commento